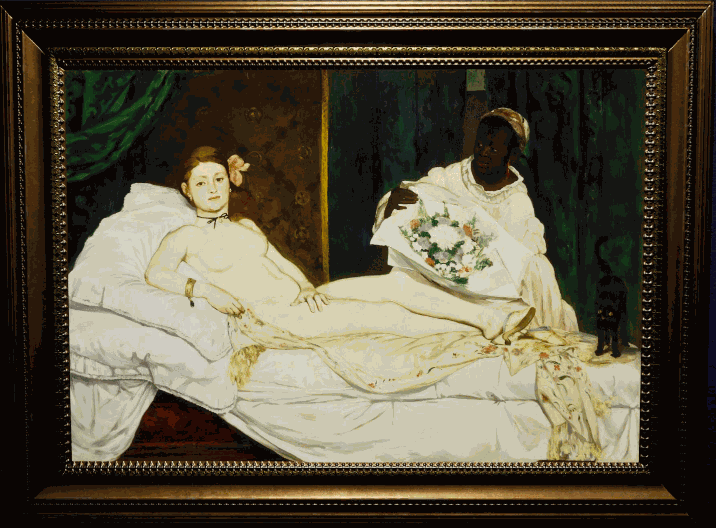

There are two women in Edouard Manet’s infamous Olympia. We know a lot about one; reclining, pert and centre stage, is Victorine Meurent. White as the driven snow, and a salon painter in her own right, she was in high demand as Manet’s go-to studio model in the 1860s. We know when she was born (1844), what her parents did (laundress, bronze embellisher) and what she made. As for the second woman, a servant standing behind Meurent/Olympia to present her with flowers, we know only her first name: Laure. Laure is black.

While there’s plenty I admire about Olympia, it seems as glaring an example of 19th Century European racism as we’re likely to stumble across. In a world where women were second class citizens, prostitutes lower still, the black woman’s status as Olympia’s servant kicks her so far down the social hierarchy as to vanish (almost literally) into the shadows.

I paint black women too; I paint them very differently. In Balancing Act, for instance, the black female body is front and centre – crucially, she’s subject rather than object a la poor Laure. While Edouard and I might agree on an appreciation of the female form, I’d like to think that Balancing Act’s contortionist is in control to an extent that Olympia (let alone her servant) could only dream of. Her body is strong, agile, and at her disposal rather than ours.

Performing, rather than exposed to us, our gaze is acknowledged implicitly – an inversion of Olympia’s openly meeting the viewer’s eye as if to say “here we go again”. Turning to Rejoinder, we see a girl with a gun. She’s shooting something from the sky – clay pigeons? On the contrary: her targets are drones. Taking aim at agents of unsolicited viewing, this is another woman not only aware of eyes on her but in control of them.

I’ve learnt a lot from Manet’s bold compositions. Symbolism, too, is a mutual interest; take Rejoinder’s staffie dog representing fidelity, or Balancing Act’s empty heart-shaped box. Likewise, Olympia is accompanied by a host of clues (beyond her nudity) as to how she ought to be read: a cat arching its back in the painting’s corner, for instance, was associated with prostitution. So was the name Olympia itself. Radiating from that futon, Love For Sale is legible at the most cursory of glances; while I’m also keen on clarity, I’d rather frame the women in my paintings as protagonists than props.

VOMA is the world's first entirely online art musum, offering a unique opportunity to hear the stories and histories of artists from across the world. Without the limitations of a physical location, access to a museum is possible to anyone with an internet connection. The museum becomes a truly communal experience where the voices of the visitors can be added to the conversation.