‘Granny told us the scariest stories about Mami Wata. If she heard we’d been swimming, she'd get really cross.’

Sahara Longe’s grandmother is by no means alone in her reverence for water spirit Mami Wata, though specific beliefs about the deity vary depending on where one is in the world. ‘She appears in so many different African countries, as well as South America and the Caribbean where she travelled with the slave trade’, explains Longe. ‘So everyone has a different story – my mum thinks of Mami Wata as albino with long blonde hair, and lots of people think she has a fish's tail… She represents money, healing – she does loads of different things,’ she continues. ‘But I like the story of fertility. If a woman couldn't have children, she would go and pray to Mami Wata who would give her a baby.’

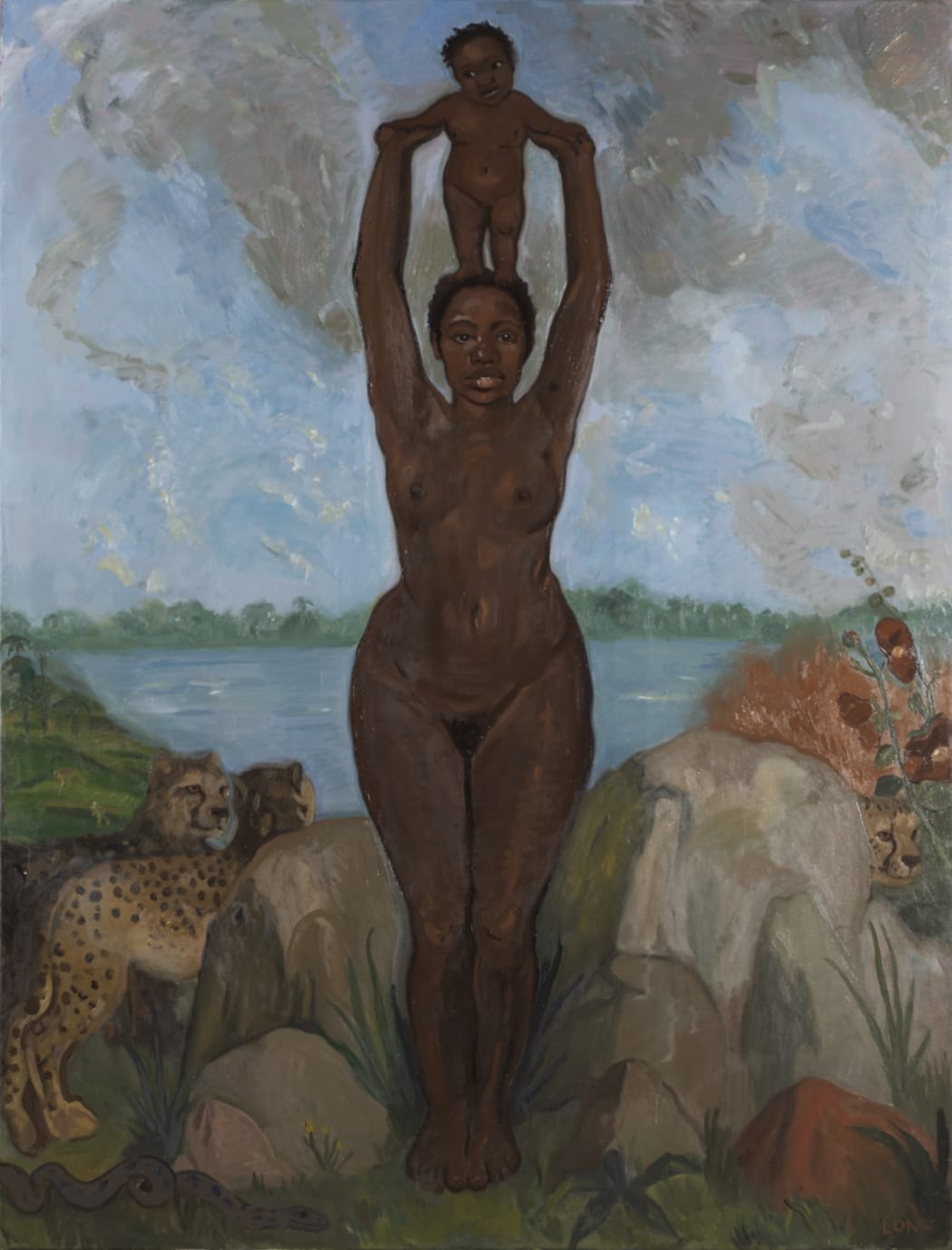

Just such a prayer is the subject of Longe’s Mami Wata, 2021. The painting – more than two metres tall and almost as wide – doesn’t depict the deity herself: rather, a happy new mother (‘it could be called Grateful to Mami Wata, I suppose’) raising a smiling infant to the sky in something like exaltation. Behind her, a trio of cheetahs are gathered in front of a body of water, stretching across the canvas’ background and finding a mirror in its impossibly expansive sky.

Flowers press into the composition from its right-hand side, blooming just beyond the frame; meanwhile, a snake slithers in stage left – a symbol of Mami Wata, and more besides. While Mami Wata will be eminently legible to those familiar with her legend, audiences more au fait with Western art history might read Eve-and-serpent or Madonna col bambino instead. Equally vibrant are echoes of classical female nudes, or Christian painting’s ubiquitous cherubs – and while such interpretations will always say more about viewer than artist, you’d be hard pressed to find a painter more steeped in the Western canon than Longe.

From Velazquez to Van Dyck, and from Titian to John Singer Sargent, history’s most feted painters have used techniques passed down through generations. At Charles H Cecil Studios, a small atelier in Florence where Longe studied, those methods are taught to this day; wielding that heft of heritage, and armed with skills honed over centuries, she approaches a canvas with all the training of a Renaissance studio apprentice. And in Longe’s hands, that masterful grasp of material and medium conjures something very different (though in other ways, very similar) to what he might have made.

I say ‘he’, because – barring very few exceptions who largely prove the rule – history’s most famous painters have been white men. According to the National Gallery’s own website, the museum holds more than 2300 works. Just 21 – less than one percent – are by women, and all those women were white; meanwhile, only 50 paintings feature a Black subject. As such, when it comes to who holds the brush and what they use it to paint, the canon has made the rules very clear indeed: all the more delicious to see them flouted so deftly.

From historical tableaus to figure studies, from portraits to sketches, the subjects of Longe’s work are almost all Black. ‘They're their own subjects. These are their own stories, not part of someone else's’, the artist explains. By engaging oil painting’s weighty tradition, Longe uses its visual shorthands to usher in identities hitherto excluded by its high walls. Turning her expertise to ‘Sierra Leonean and West African mythology’ for the first time, Mami Wata addresses ‘the story [she] know[s] best’.

Longe’s canvases draw elegantly – and unapologetically – on Old Masters’ subject matters as well as their methods. Take the cheetahs to the left of Mami Wata’s central figure: ‘they’re Titian’s cheetahs’, says Longe, referencing the animals in sixteenth century masterpiece Bacchus and Ariadne. ‘I think all painters steal ideas – and I like finding them. I love going through, say, a Rubens, and noticing, ah, Titian used that in his painting’, Longe says. ‘You find that all the time, and I love it. You learn how they did it by doing it yourself’, she muses; ‘not quite an homage, but almost.’ Vaunted canvases, broken down for parts to mine and splice – for Longe, the history of painting is a two-way street of inspiration and output.

Mami Wata’s powers are similarly multidirectional, encompassing debit as well as credit. Having granted a desperate woman their longed-for baby, the water spirit requires substantial payment; ‘in return for a child, the woman would lose her looks, or maybe money. She wouldn’t be successful anymore’ explains Longe. ‘She would have to give something up for the baby’ – and for all the cultural specificity of Mami Wata’s legends, what sacrifice is more celebrated than that made by a mother for her child?

Be it physical or professional, emotional or practical, women around the world are still expected to forfeit everything from careers to identities on the altar of motherhood. Of course, that equation is anything but new: think of depictions of the Pieta, Mary confronted with her adult son’s broken body lolling over her lap and cradled like a baby. For many, it’s the ultimate symbol of motherly devotion and agony: ‘I love the Madonna and Child thing’ muses Longe. ‘That idea of sacrifice is such a powerful concept, but [in Mami Wata] the baby is in the air – she's very proud of the baby, and she’s looking at the viewer.’

Wherever they are, and no matter the era, human beings reliably conjure stories to explain their place in the world. Searingly eloquent, Longe’s practice repurposes our most revered narrative templates to make space for people and perspectives historically written out. In a Venn diagram of overlapping circles, ‘Mami Wata’ and ‘Madonna’ have less in common than the people who invoke them – yet, ‘I think most women can understand what she's doing’, says the artist of her piece’s protagonist.

I think so too. Whether you find yourself coveting the new parent’s position or simply sympathising with her, some ideas – mothers and babies, wanting and getting – are universal. Others are liable to get lost in translation: and if we’re thinking in terms of language, then perhaps the best term for Longe’s vision is ‘bilingual’. Leaping between visual dialects with enviable ease, we are lucky enough to travel some way with her.

By Emily Watkins.