Abe Odedina’s Cutting Edge surveys the myriad resonances that ‘cutting’ might have in the lives of human beings. Giving shape to established mythologies with one hand and summoning his own uncanny cast of recurring characters with the other, cutting emerges as a very Odedinan subject indeed: both monumental and unremarkable at once.

Characteristically languorous, illustrative and iterative, many of Odedina’s tableaus are purpose-painted for the exhibition. Others are drawn from his prolific oeuvre, where scissors, shears and scalpels have long abounded. Drawing on a practice not just overflowing with symbols but frequently hinging on them, Cutting Edge sets scenes in sites of everyday cutting – butchers, barbershops, a birthing room in The first cut is the deepest – and the realm of allegory too: Why why why? stars Delilah, the Old Testament’s most notorious hairdresser.

As Odedina’s work makes clear, it’s hard to overstate the influence of slicing, splicing, smelting, scarring, trimming and clipping in shaping lives day-to-day – arguably, civilisation itself is built on cutting’s capacity to refine as well as destroy; something of a double-edged sword. Metal blades produced by iron- and bronze age techniques (useful for farming and fighting) propelled humans to new technological heights. Knives and ploughs are no-nonsense, and the cuts we make with them are straightforwardly quantifiable: tonnes of crop harvested, number of battles won. Equally, Odedina’s Cutting Edge carves space for less tangible – more magic – entries in cutting’s encyclopaedia.

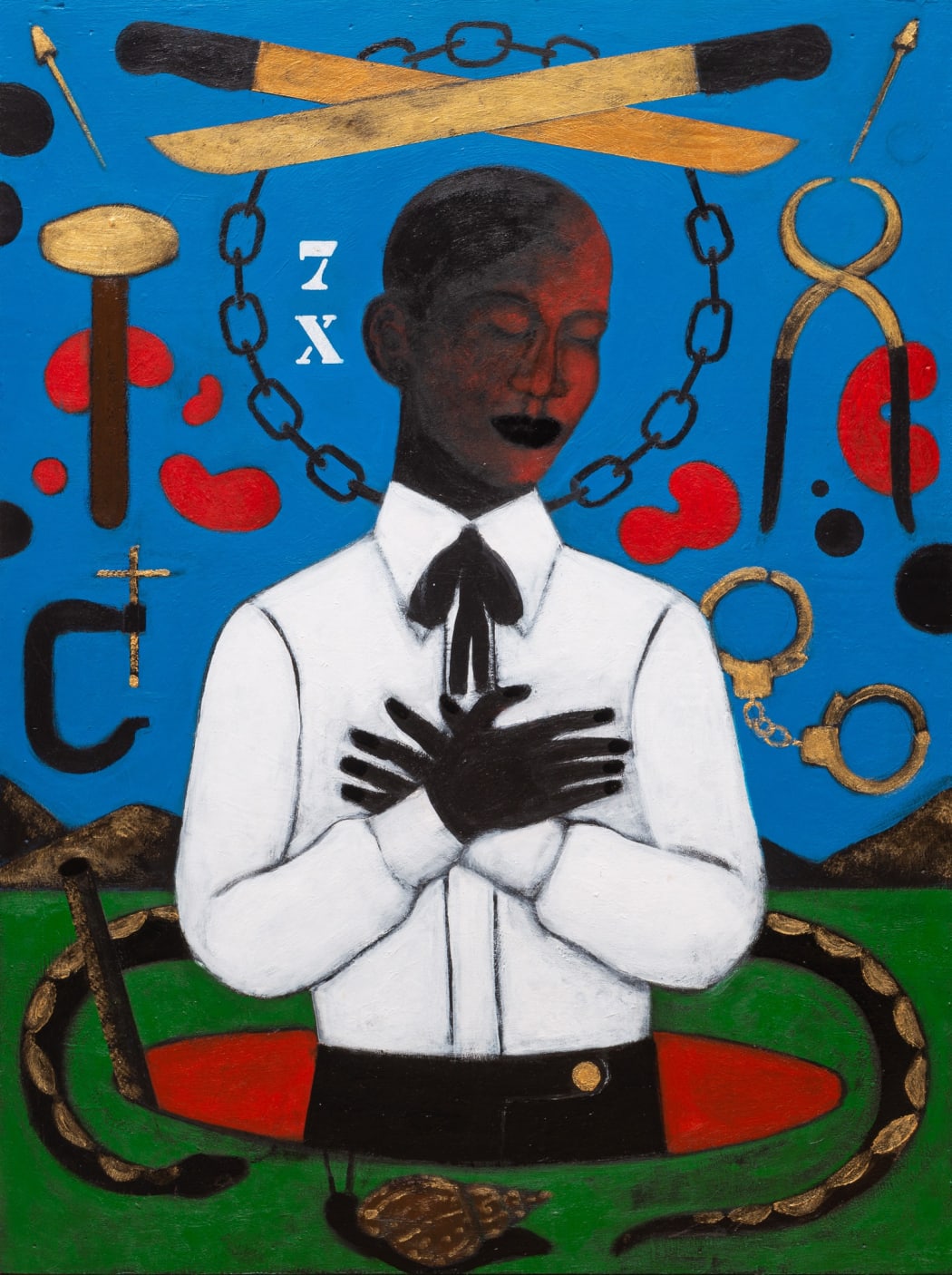

It’s from smelting’s sea of new possibility that Yoruba deity Ogun arose in Nigeria, Hepaesthus in Greece, Kagu-tsuchi in Japan; wherever there was blacksmithing, humans ushered in a god to oversee it. Only right – this is serious business; one can no more uncut an anvil or an arm than unring a bell. On this knife edge of being and belief, processes like scarification and circumcision – or the ritual cutting and not-cutting of hair – test a blade’s cold logic against warm bodies.

When it comes to flesh and blood, cutting can be lethal; skin is delicate, razors are sharp, and so the places where they meet (even if only to remove hair from scalp) engender shortcuts to intimacy. In Cut a fine figure’s barbershop, a black panther swaggers just out of sight, small talk gives way to quiet epiphany and a boy is initiated into his high street tribe. Viewers steep in the salon’s comfortable silence like tea.

Metaphor has long acknowledged the power of the cut in conveying precision, ruthlessness – in English, to cut a fine figure, deliver a cutting glance, cut to the chase, cut someone down to size or cut one’s losses, are all idioms loaded with a blade’s implicit finality. When a director shouts CUT! she stops a scene in its tracks, and when we pronounce something to be on the outer reaches of culture’s avant garde, we call it cutting edge. In Odedina’s hands, that title is wielded with something of a sideways smile.

Applied to the exhibition entire as well as a single painting – depicting Ogun, red as the iron ore he comes from and surrounded by his tell-tale metalworking tools – Cutting Edge remains delightfully malleable despite its surface simplicity. Philosophically speaking, cutting multiplies as well as divides. From Odedina’s vantage point, gulfs between a bread knife and a sculpture, a scalpel and a painting, between a deity and a barber or multiplication and division, begin to look more like fluid than fissure.

By Emily Watkins