A bathtub overflows, spilling a pool of iridescent, technicolour bubbles across a wobbly checkerboard floor. More bubbles rise up and burst into sparkles, as, all the while, a rubber duck bobs in the swirling bathwater. Is that a cheeky smile playing around the corners of its cartoonish beak? Or am I just imagining things?

Looking at Pippa El-Kadhi Brown’s work feels like hallucinating. Her paintings are a shimmering dream, a fading memory, a trip and a trick. All is not as it seems. Inanimate objects appear imbued with life – poised to move, shift and transform at any moment. Doors stand ajar, windows fly open and staircases lead off into unknown realms. You are offered tantalising glimpses beyond the immediate image; El-Kadhi Brown’s scenes seem to unspool and expand, always pushing or beckoning outwards. Or are those thresholds pathways leading into other paintings? Even quick glimpses at El-Kadhi Brown’s work are enough to start seeing double. Checkerboard tiles become rugs, become tabletops, become chessboards. Oranges seem to roll across the floor from one domestic locale to another. A small charcoal work, Sunday Best II, is echoed on the wall of a larger painting. Moving between El-Kadhi Brown’s works can feel like playing an elaborate game of snakes and ladders. Indeed, look long enough, and you might feel like you’ve slipped through the canvas and become an inhabitant of this surreal, luminous world – a presence haunting these hallucinatory rooms, like one of the artist’s recurring ghostly figures.

Go back to the bathtub scene for instance. In Strings in Hand, The Puppet Master Plays, With Great Shining Talons for Claws, a door stands open, and on the other side from the surging tub a bulbous yet wispy figure is curled on an egg-shaped seat. At a glance they could be another bubble. But what is their true role here? Did this figure turn on the tap next door? Or are they about to be startled by the surging water? Who is doing the haunting and who is being haunted?

“Water, for me, it’s such an idea of a presence, especially a tap or a shower,” El-Kadhi Brown tells me. “When there’s doorways, it always gives that idea of something beyond,” she adds. “Even things like an orange on the floor – there’s actions that have taken place to cause that to happen. A running bath: someone’s had to turn it on,” she says. “There’s this action that’s taken place and, if you leave your tap on, it also causes havoc.” In El-Kadhi Brown’s world, in other words, an orange isn’t just an orange and a dripping tap is never just a tap: it’s a sign of life, movement, action; the unknown and the still-in-becoming. It epitomises “the idea of ghostly encounters”. “It’s not static,” El-Kadhi Brown says of her restless visual world. “The viewer’s always witnessing either something happening, or having just happened, or about to happen. There’s always this lingering idea of a presence somewhere.”

Of course, really it is El-Kadhi Brown who is causing havoc; she who is setting up these ghostly encounters. Indeed, it strikes me that the bathtub painting’s title – Strings in Hand, The Puppet Master Plays, With Great Shining Talons for Claws – could be a good description of the artist herself. Across all her work, El-Kadhi Brown comes to resemble a puppet master playing – moving her spectral, ballooning figures and recurring symbols from room to room, giving them props and toys, and creating something akin to a dance or stage-designed spectacle. Yet, for all the soft pastel colours and beams of radiant light, there is a sense of threat here too. These works are ethereal and luminous, but they are also strange, unsettling. As she has said herself, El-Kadhi Brown’s paintings “playfully disembowel the anatomy of the domestic environment, gutting it from the inside out.” The puppet master has talons; claws.

As well as motion then, contradiction is also inherent to El-Kadhi’s work. Her paintings’ “delicate, almost pastel-y style” have what she describes as an “angelic feeling”. Yet, she also notes that they have “a strange, shadowy feeling about them”. Nothing is as it seems because nothing is only one thing. Everything is both angelic and shadowy; haunted and haunting; serene and causing havoc; playful and in the midst of disembowelment.

In Cumulus, for instance, botanical shapes sprout against a buttery yellow background, and a window’s shutters are thrown open to a dusky lilac sky, bleeding into pink. In the centre of the canvas, a wavering pink puddle is covered with fluffy white clouds, which drift over the whole painting in a line, like a dance from Disney’s Fantasia. El-Kadhi Brown says it is “the most ‘feminine’ painting” she’s done, suggesting it “feels very stereotypically soft.” At the same time though, she also highlights the work’s essential “strangeness”: the inside and outside seem to have merged, the sky surging into the room, the plants threatening to engulf everything. And is that pink tangle a ghostly figure too, or more scraps of cloudscape? There is no violence in this scene, but still the soft femininity of the piece comes with an undercurrent. Things are unsettled. It is impossible not to think that some kind of funny business is going on.

There is a similar instability and alluring inconsistency at work in Moth by Moonlight. Another bubbly ghost sits curled up in a curve – the same figure from the bathtub scene? Here the colour palette is somehow both darker and lighter. Through another open window the sky is now a deep blue – the same midnight shade that suffuses the interior scene. Except, not entirely. For every slice of night, there is a shimmering beam of light. At the painting’s heart a radiant rhombus is cast across the room, enveloping the figure. This impossible glow calls to mind Magritte’s infamous surreal work Empire of Light, with its similarly impossible combination of night and day; its house with windows but no doors. El-Kadhi Brown’s work may be softer, more lighthearted, contemporary and kitschy, but these resonances make each piece into a hall of mirrors. Here is Magritte with an Instagram explore page; here’s Matisse playing Mario Kart.

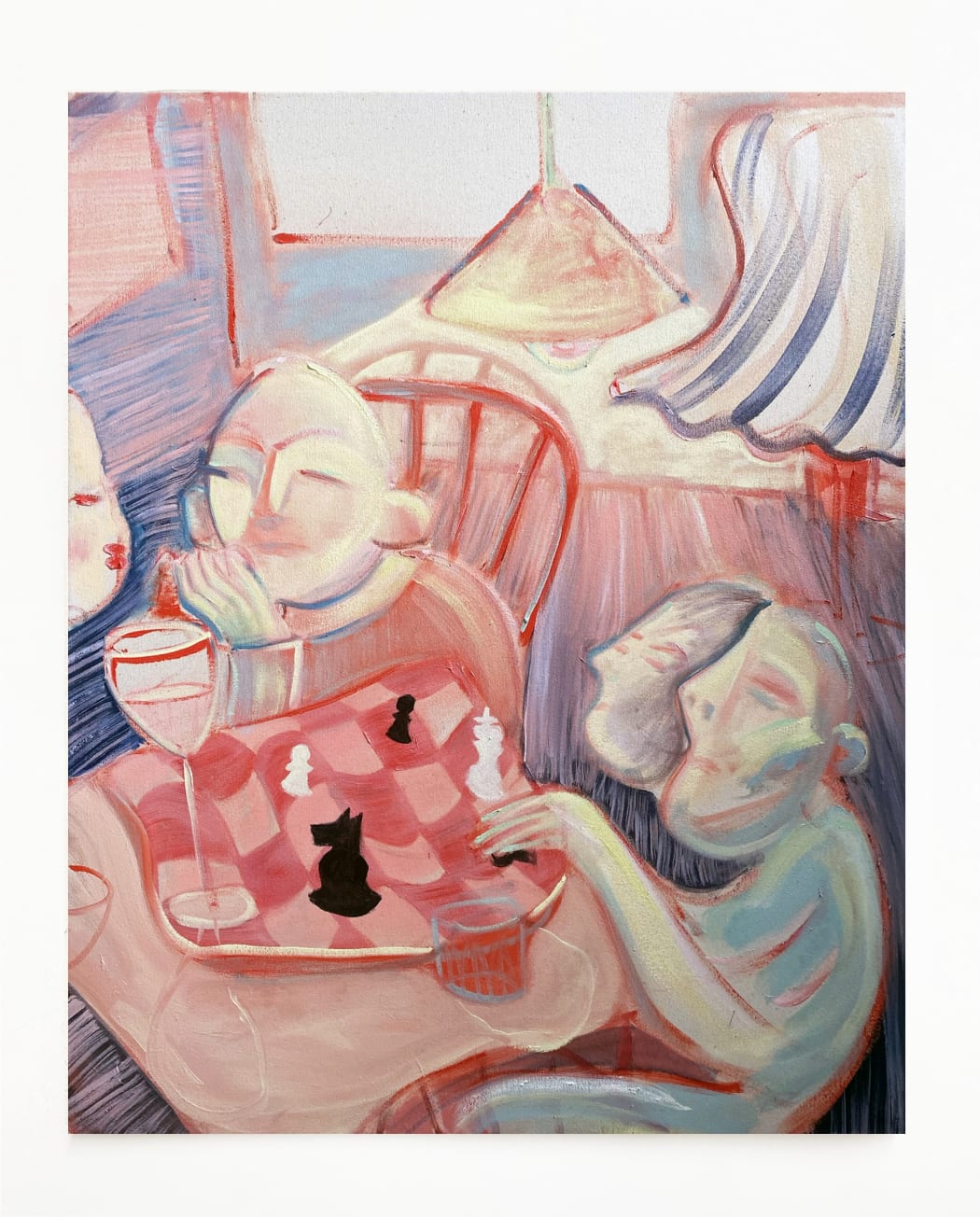

Perhaps “threat” is too strong a word for El-Kadhi Brown’s figures and figments then. Unlike angels or ghosts, they don’t linger in order to frighten or offer salvation. They are more involved. Holding an enormous jelly, playing chess, showing their round, ethereal bottoms, they begin to look like tricksters, rascals. “I often think about the figures in the paintings to be these ghostly presences,” El-Kadhi Brown says. “But not necessarily a spooky bad ghost.” Later, she tells me she imagines her domestic setting as “a space that’s haunted, but not necessarily in a spooky way.”

By way of an example, she says she has recently been hooked by a figure from Slavic folklore: the Domovoy, which she describes as a “spirit slash guardian that looks after the home”. Their guardianship wasn’t purely protective though – “they were guardians, but they were a bit meddle-y,” El-Kadhi Brown tells me. “They’re not really there, they’re just running around, maybe causing chaos, maybe you thought you’ve seen them but they’re just brushing past in the next room.” In other words, like El-Kadhi Brown’s bubble creatures, they’re up to funny business – truly inhabiting a space, rather than strictly haunting it.

Here then, we come to reveal the beguiling contradiction at the heart of Haunt. On one level, the title of course conjures notions of visitations – spirits and poltergeists and Domovoys and ghosts. “But also, this idea of “haunt” is what you’d call a place that you frequently visit,” El-Kadhi Brown says. “A place that you feel comfortable in.” Your home is a haunt too. See, you’ve slipped through the canvas again. Pull up a chair next to the chess-players of Ghost Party. Get comfortable. Look at yourself as a haunting presence.

Just as Strings in Hand seems to sum up El-Kadhi Brown’s artistic approach, Ghost Party seems like a fitting description for her entire oeuvre. This is a playful disembowelling, a pleasurable haunting. The ghosts aren’t just present, they’re partying. Okay, they might cause a bit of havoc. They might flood your house. But that’s the risk at any good party, right? Go on, step over the threshold, grab a drink, and have a look at what’s going on upstairs.