Opening the door to his south London home wearing his signature blue overalls and spectacular spectacles, two rambunctious dogs barking at his heels, Abe Odedina offers to put on some coffee and we instantly launch into a discussion about his paintings and the inexplicable meanings of life that they investigate.

“What I want to do is ask the questions that we all ask,” he profers. “We are hemmed between two massive mysteries. We don’t know where we came from and we don’t know the details of how we’re going to go out. So we deal with that gap in between, in marvellous ways if we’re lucky. This pretty hopeless situation is the human condition that unifies us all.”

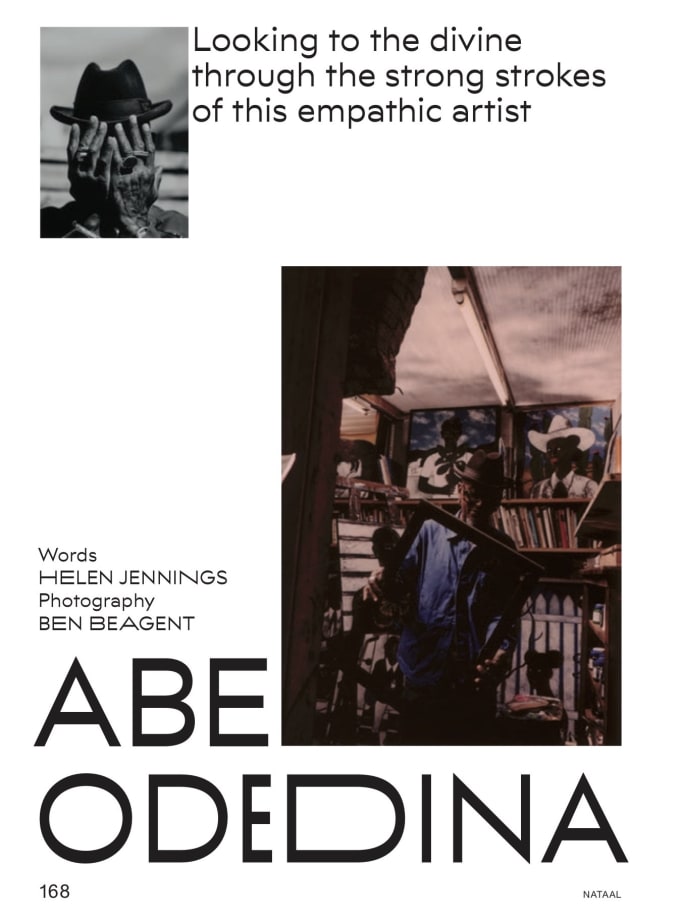

Odedina shows me through the house, which reveals itself to be a welcoming shrine; every surface covered with splendid objects of joy. Haitian Vodou flags, Mexican votive paintings, West African barbershop signs, wonky ceramics and ritualistic sculptures of every persuasion all hang out harmoniously together. Meanwhile at the end of the garden sits Odedina’s humble studio where his paintings — acrylic on sturdy plywood — are unceremoniously piled up. Striking in their use of contrasting colours, seemingly simple in composition and utterly wondrous to behold, his works draw on folk art, magic realism and the traditions of African studio photography to create inquiring and playful scenes. Most of them feature a dignified figure doing something intriguing — levitating, dancing, shooting a bow and arrow, juggling, playing the fiddle, swallowing a sword, riding a huge sea creature, pointing a telescope to the heavens. They’re at once honest and baffling, blunt and beguil- ing, and together they create a world of dreams that feels delectably close to home.

“The figurative traditions that influence my work most powerfully come from the makers across Africa. Central to those is using the figure to represent many complex ideas around cosmology, daily life and our aspirations,” he explains. “Even though I make distinct and strong paintings, they are images of ambiguity. Each one embodies a mystery that dissolves while you consider what the hell it means, and then begins to stretch in all directions. It’s a call-and-response between the work and the viewer.”

The paintings here today are from his current body of work, Birds of Paradise, which was recently presented by Ed Cross Fine Art at London’s Copeland Gallery and curated by Katherine Finerty. For Odedina, these iridescent feathered friends who go about living their best lives with glee, reflect his ongoing preoccu- pation with the human endeavour to find fulfilment in whatever form that might take, and against all seeming odds. In these current troubling times, the idea of utopia may seem remote and even damaging, but Odedina believes we remain hardwired to seek it out, whether physically, mentally or ideologically.

“Paradise is a lovely idea that we invest in. Most cultures have some notion of this other place; the promised land. My sense is that paradise is running very close to our normal lives, and available to us when we hit the right note. It might come with a message on your phone. Finding the right shade of lipstick. Even a good cup of coffee. In bed sometimes we get a glimpse of the divine when we have a good fuck. That magical moment just before sunrise is paradise and it happens every day.”

The show’s namesake painting is a rare self-portrait showing the artist having a tattoo done, something he did in real life every Friday for over four years until his entire body was covered in small works of vernacular art. The idea was not to masterplan a perfect breathing canvas, but to explore the physical plasticity and freedom of expression of one’s body — a vivid example of one of his own personal paradises.

Odedina came to painting relatively late in life. Born in Ibadan in 1960, he moved to the UK to study architecture and went on to establish his own practice. Then on a trip to Salvador in 2007 with his family he was confronted with Candomblé, a religion fusing Catholic and Yoruba beliefs that spoke to him deeply. “I knew a lot of these gods from growing up in Nigeria so when I saw how phenomenal they were in Brazil and how they offered people so much comfort, strength and beauty, it was one of those points where I realised life had to change for me,” he recalls. “There was also something extraordinary about the vigour of the popular arts in daily life inspired by these deities. That search for harmony was worth paying attention to.”

And so Odedina went for a divination and discovered that his two orishas were Șàngó, god of thunder — who for him represented the future —and Ogun, the primordial god of iron and war. He bought a second home in Salvador, started painting, and soon enough his new passion became his everything. These and other Yoruba deities and their related iconographies now live in his works and help him to further investigate the universal struggles and hopes that feed our shared humanity. “Why are we looking for the differences between science and belief? As twenty-first-century creatures we can go beyond empirical information to have a word with all of these wonderfully poetic constructions and have full reign to pull ideas out of them,” he says.

Another one of his myriad inspirations is Frida Kahlo, whose artistic voice he embraced after visiting her home in Mexico City. His diptych painting, The Adoration of Frida Kahlo, was nominated for the BP Portrait Award in 2013 at the National Portrait Gallery, and helped him make the transition to being a full-time artist. Since then he has enjoyed solo shows at 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, The Department Store and Brixton East, and has joined group exhibitions at Stephen Friedman, Knight Webb Gallery and The Royal Academy. With plans to show in Los Angeles and Lagos next, this deserved success speaks to the emotional intelligence of the work and the man who makes it. His paintings celebrate our triumphs, tragedies and flaws with a true heart. Now, how about that coffee?